Subwatershed Health in the Upper Little Tennessee River Basin

Western Carolina University’s Keith Gibbs discusses what he and his research team are doing to advance subwatershed integrity in the Upper Little Tennessee River Basin.

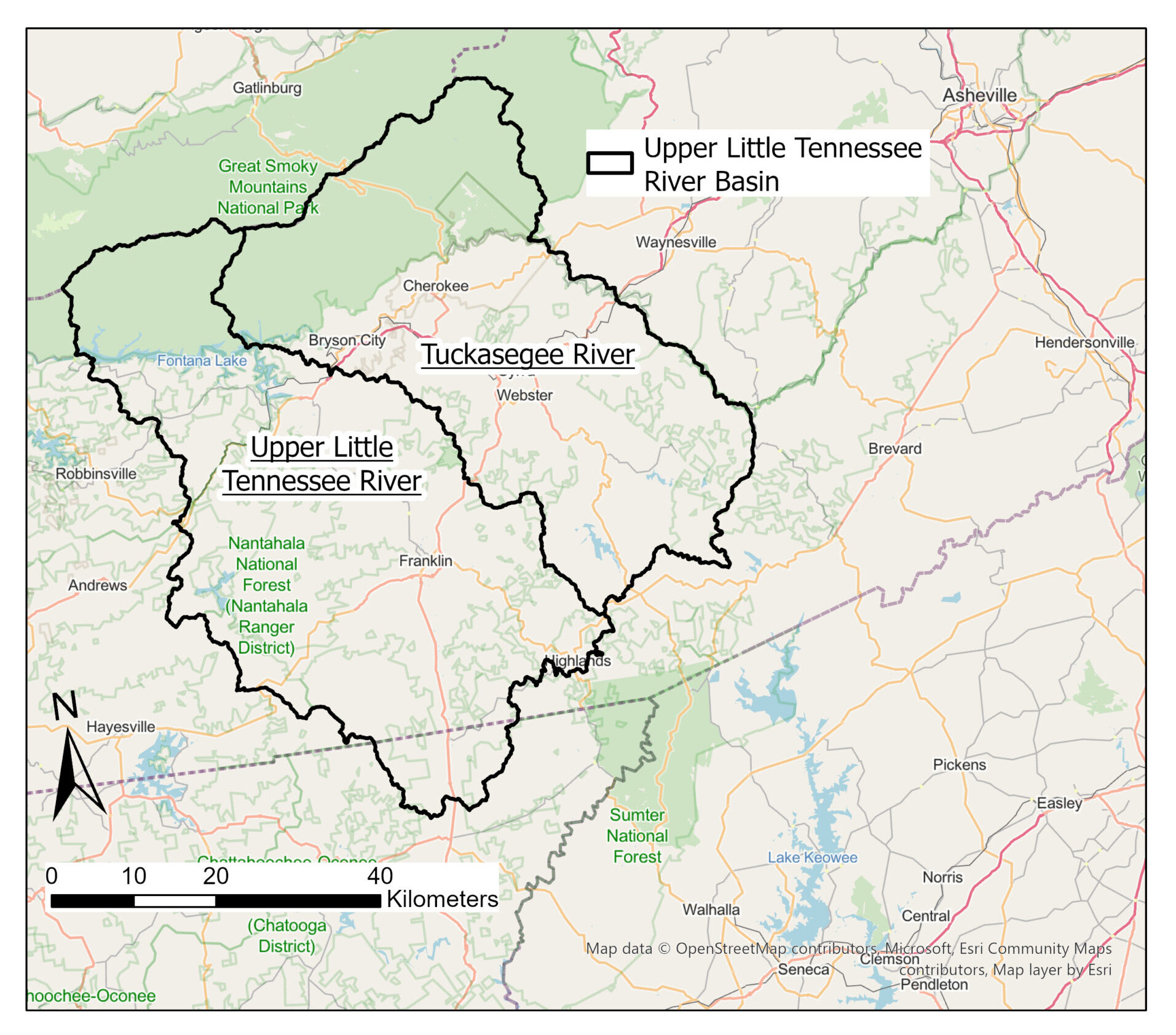

Western North Carolina, as well as the Upper Little Tennessee River basin – part of the larger Little Tennessee River system that flows from Tennessee, through western North Carolina and into Georgia — has been impacted by prominent water quality issues, including increased runoff and sedimentation from nearby development, agricultural runoff, septic system damages, stream bank erosion resulting from absent riparian buffers, and many others. In fact, many of the stream segments in the western region of the state have been labeled as impaired by state regulatory agencies due to the increased turbidity, or cloudiness, as well as fecal coliform bacteria and weakened fish and macroinvertebrate populations.

Keith Gibbs, an assistant professor at Western Carolina University’s (WCU) Geosciences and Natural Resources program, is currently in the midst of research regarding the issue of Western North Carolina water quality, specifically looking at the Upper Little Tennessee River Basin. Through assessment of land use and stream health of the upper basin region, Gibbs is developing scoring criteria to categorize and rank the ecological integrity of the subwatersheds – smaller watersheds that come from much larger ones — located within the basin. His research team also wants to “identify and draw attention to human activities within the upper Little Tennessee River basin that have the greatest negative effect on aquatic ecosystem health,” he told WRRI recently.

Much of the water system deterioration has come from population growth and human developments, leading to rising rates of sedimentation and eutrophication — which are two of the biggest threats facing water resources in North Carolina. Gibbs designed this project to enable resource managers to better apply corrective measures, specifically throughout the mountainous area of the state, by uncovering the landscape-level impacts on western water resources.

John Fear, deputy director for the Water Resources Research Institute (WRRI) programs, notes the importance of funding Gibbs’ project, stating, “Watershed mapping is a great tool to help better manage our water resources. By going to the subwatershed level, this project will help us understand what changes are driving the observed water quality declines.”

WRRI caught up with Gibbs to see how his research has progressed and what his goals are for his WRRI-funded project. Gibbs is the lead principal investigator for this project, working with co-principal investigators Diane Styers, the department head and associate professor at WCU’s geosciences and natural resource department, and Thomas Martin, the department head and associate professor in WCU’s biology department.

A Project in Motion

While this project is still in its early stages, Gibbs and his team have hired several undergraduate research technicians who are taking on the spatial analysis feature of the project, using geographic information systems (GIS). The team is also acquiring water quality monitoring equipment that will provide continuous monitoring of in-stream conditions of the basin’s subwatersheds during the span of the entire study. These water quality data loggers will be deployed at every sample site to specifically measure temperature and turbidity.

Gibbs’ research falls in line with his previous work, which focused on land-use patterns in relation to endangered aquatic organisms. Gibbs states that his current project “is an expansion of this strategy with a broader focus.”

It also relates to his overall research interests and endeavors, as he has worked his entire career to promote the protection and restoration of aquatic systems in western North Carolina — from improved water quality of water systems to strengthening the ecological integrity of those systems through regional partnerships.

To help with his research needs this time, Gibbs and his team are again creating partnerships, working closely with a broad collection of agencies and organizations located within the Little Tennessee River region. This includes the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, the Little Tennessee Native Fish Conservation Partnership, Mainspring Conservation Landtrust, North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission and the Tennessee Valley Authority.

Mentioned in a support letter for Gibbs’ research proposal, Luke Etchison, an aquatic wildlife biologist at the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission, elaborated on why he and the Commission find this project to be so important: “My primary focus in the Little Tennessee River watershed is to restore mussel and fish varieties. Without projects like this that will guide education, restoration and management, long-term stability and recovery of aquatic variety in the watershed will be limited.”

Gibbs sees collaboration as an integral part of this research, due to the impacts of ecological instability in the region, as it involves the work and lives of many in the aforementioned organizations and community institutions, especially the indigenous communities that possess a significant connection with the Little Tennessee River’s health.

Hopes & Goals

While Gibbs and his team are still in the process of collecting data from their selected subwatersheds in the Upper Little Tennessee River Basin, he does have several goals when it comes to applying the research he and his team are currently undertaking.

“We hope to identify subwatersheds and stream reaches in the greatest need of conservation, to help prioritize future conservation actions in coordination with research partners,” he explains, noting that western North Carolina is his target location.

He anticipates this research will relate to other water systems, “We hope to create a template to assess and score subwatershed health that is easily transferable to other regions in North Carolina and the southeastern U.S.,” he shares.

Working with the groups like the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, Little Tennessee Native Fish Conservation Partnership and other critical organizations in the targeted Upper Little Tennessee River Basin area, Gibbs’ team can use the findings to aid in detailing the specific human pursuits that damage the ecology in the nearby subwatersheds. This will assist an ultimate goal: By communicating which human impacts are damaging to the upper basin, the team will help local communities and organizations understand environmental impacts. The data will also be openly available through various websites, while the GIS data will be employed for community outreach and education purposes.

Lastly, Gibbs mentioned the collective impact of subwatershed health and what can be done to help. “In many instances,” he says, “we can improve subwatershed health with modest changes to current land-use practices, which is important because we all live downstream.”

Overall, this collaborative research project will hopefully gather findings that will help strengthen impacted subwatersheds in the Upper Little Tennessee River Basin, as well as others across the western region of North Carolina. Gibbs and his partners hope to give communities the information they need to improve subwatershed quality.

View summaries of the other 2021-22 WRRI faculty research projects by clicking here: WRRI’s 2021 Faculty Researchers Announced.

Opening Image: Little Tennessee River; Source: USFWS on Flickr